Fiji Islands: A Paradise of Crystal-Clear Waters, Rich Culture, and Unspoiled Beauty

The Fiji Islands, a magnificent archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, embody a paradise where the crystal-clear waters meet the warmth of its people and the richness of its culture. This island nation, with its sprawling landscapes from the lush hills of the larger islands to the pristine beaches of its coastal areas, invites the world to explore its beauty and traditions. A visit to Fiji is more than a holiday, it’s an immersive experience into a lifestyle where the harmony between nature and culture creates a unique tapestry of life. Each island, from the major islands to the smaller, secluded ones, contributes to the mosaic that makes Fiji a south pacific paradise. Here, the spirit of Fiji welcomes all, offering a blend of adventure, relaxation, and cultural richness that is unparalleled. Among the many jewels of this paradise is Viti Levu, the largest island, home to the capital city, Suva, a hub of Fijian culture and the gateway to exploring the splendid diversity of Fiji’s islands.

Exploring the Island Nation: Diversity in Landscape and Culture

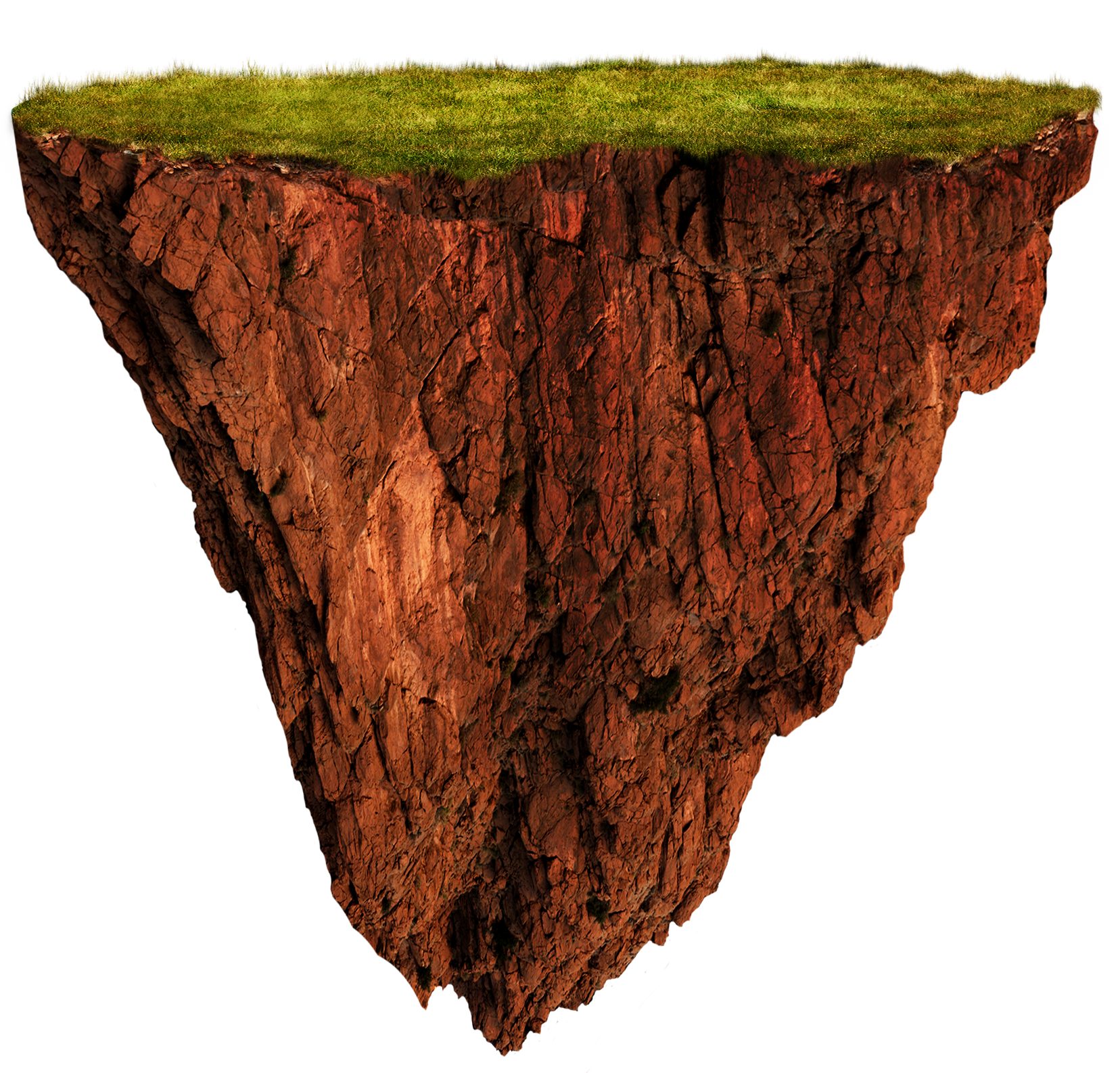

Fiji’s landscape is a testament to the island nation’s diverse natural beauty. From the rugged mountains that adorn the island of Viti Levu to the serene waters of the Great Astrolabe Reef, the geographical diversity offers something for every type of adventurer. The Fiji Islands are not just about picturesque beaches, they are a land of contrasts, where the dense rainforests in the interior give way to the serene beauty of the coral reefs surrounding the islands. The culture is equally diverse, with traditional Fijian food offering a taste of the local heritage and the vibrant communities showcasing the warmth of the Fijian spirit. Island hopping between the main islands and the other islands, like the Mamanuca and Yasawa groups, reveals the unique character and beauty of each. The Fiji experience is about exploring this diversity—landscapes that shift from east to west, and cultures that blend the traditional with the modern. https://essaypro.com/write-my-discussion-board-post is an invaluable resource for students needing to contribute to course discussions on global topics, such as the Fiji Islands. This service ensures that posts are informative, engaging, and reflective of the student’s understanding of Fiji’s cultural, environmental, and tourism aspects, enhancing online class discussions with well-researched contributions.

The Heart of Fiji: Experiencing the Uniqueness of Island Life

The heart of Fiji beats strongest in the everyday life of its people and the natural splendor that frames their homes. Life here flows with the rhythm of the island, from the bustling markets of Nadi International Airport’s nearby towns to the quiet, majestic rise of the mountains in the interior. The Fiji experience is as much about engaging with the local culture as it is about enjoying the natural environment. Traditional Fijian, seen in the craftsmanship of bark cloth or in the elaborate ceremonies, offers a glimpse into the soul of the islands. The importance of community and sharing in Fijian culture is evident in every meal shared and every story told. This sense of belonging extends to visitors, who are welcomed to partake in the island life, whether it’s through a kava ceremony or a communal meal. The beauty of Fiji lies not just in its landscapes but in its ability to make every visitor feel like part of the island family. For those interested in the breathtaking natural beauty and rich cultural heritage of the Pacific, the best custom writing services can provide in-depth essays on the Fiji Islands. These essays explore the islands’ history, tourism, environmental challenges, and cultural significance, crafted by writers who specialize in geographical and cultural studies to ensure accuracy and depth.

Planning Your Visit to Fiji Islands: Must-See Destinations and Tips

When you plan to visit Fiji, timing and destination selection are crucial for maximizing the Fiji experience. The best time to visit is during the milder months, from April to October, when the weather is pleasant, and the prices are generally lower than in the peak season. Starting your journey at Nadi International Airport, located on the island of Viti Levu, offers easy access to some of Fiji’s most iconic locations. Utilizing a coursework service can help you prepare better for such travels, ensuring you have all necessary information and plans in place. A trip to Denarau Island, with its luxury resorts and package deals, provides a gentle introduction to Fiji’s blend of natural beauty and hospitality. From there, island hopping to the Mamanuca and Yasawa islands is a must for those seeking the quintessential tropical paradise experience, with their renowned coral reefs and pristine beaches. For a deeper dive into Fiji’s culture, a visit to the Fiji Museum in the capital city, Suva, located on the island’s eastern coast, is enlightening. Additionally, exploring the less frequented Lau Islands or embarking on an adventure to the Great Astrolabe Reef offers a glimpse into the unspoiled beauty of Fiji’s outer islands. Travelers are advised to explore the diverse landscapes and cultures of both the two main islands and the myriad of smaller isles for a comprehensive Fiji experience.

The Other Islands of Fiji: Discovering Hidden Gems Beyond the Mainlands

Beyond Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, Fiji’s fourth largest islands, lies a world of untapped beauty waiting to be discovered. The other islands of Fiji, such as the remote Lau Islands and the rugged landscapes of the Yasawa group, offer a sanctuary for those looking to escape the more tourist-trodden paths. For those needing academic assistance while exploring these paradises, our platform also offers an argumentative essay writing service to help you manage your studies seamlessly. These islands present an untouched version of the South Pacific paradise, with their traditional villages, ancient customs, and breathtaking natural landscapes. The Lau Islands, for example, are renowned for their untouched beauty and traditional Fijian way of life, offering an intimate experience of the island nation’s soul. The Yasawa Islands, on the other hand, are famous for their dramatic cliffs, crystal-clear waters, and secluded beaches, making them ideal for those seeking peace and adventure in equal measure. Island hopping in these regions not only uncovers the natural beauty of Fiji’s islands but also the richness of its cultural tapestry, woven over millennia.

Fiji’s Marine Majesty: Adventures in the Crystal-Clear Waters

The Fiji Islands are a dream destination for water enthusiasts, offering some of the most spectacular marine adventures in the Pacific Ocean. The crystal-clear waters surrounding Fiji are home to some of the world’s most beautiful coral reefs, teeming with vibrant marine life. From snorkeling in the shallow waters of the Mamanuca Islands to diving in the Great Astrolabe Reef, the underwater experiences are unparalleled. For those who prefer to stay above the surface, kayaking and paddleboarding in the calm waters of the lagoons offer a peaceful way to explore the coastal areas. The adventurous can embark on deep-sea fishing expeditions or surf the legendary swells off the coast of the larger islands. Fiji’s marine majesty is a testament to the island nation’s commitment to preserving its natural beauty, offering a marine experience that is both exhilarating and respectful of the environment.

Cultural Richness and Traditions: The Soul of Fiji

Fiji’s soul is deeply rooted in its cultural richness and traditions, which are vividly alive in the daily lives of its people. The Fijian culture is a tapestry of traditional practices, rituals, and art forms, from the intricate designs of the bark cloth to the communal preparation of traditional Fijian food. Visitors have the unique opportunity to immerse themselves in this rich cultural heritage, whether through participating in a traditional kava ceremony, watching the mesmerizing Fijian meke dance, or exploring the local markets for handicrafts.

The respect for tradition is palpable throughout the islands, offering a deep connection to the land and its ancestors. This cultural journey is complemented by the warmth and hospitality of the Fijian people, who welcome visitors with open arms and share their traditions with pride and joy. Engaging with Fijian culture offers a deeper understanding of the island nation’s identity and the values that sustain its communities.

Conservation Efforts: Preserving the Natural Beauty of Fiji for Future Generations

The preservation of Fiji’s natural beauty and cultural heritage is of paramount importance to both the Fijian government and local communities. Conservation efforts are underway across the islands to protect the delicate ecosystems of the coral reefs, forests, and marine areas. Initiatives such as sustainable tourism practices, community-based conservation projects, and the establishment of marine protected areas are central to these efforts. The aim is to balance the needs of tourism with the imperative of conservation, ensuring that Fiji remains a paradise not just for the current generation but for those to come. Visitors are encouraged to participate in these conservation efforts, whether through responsible tourism practices or supporting local initiatives. The commitment to preserving Fiji’s natural beauty is a testament to the island nation’s dedication to its environmental heritage and the global community’s shared responsibility for our planet.

Fiji’s islands offer a world of experiences, from the allure of its tropical landscapes and crystal-clear waters to the depth of its cultural heritage and the efforts to preserve its natural beauty. Whether you’re seeking adventure, relaxation, or cultural immersion, Fiji provides a backdrop that is both diverse and captivating. A journey to the Fiji Islands is not just a visit, it’s an exploration of the heart and soul of a paradise that continues to inspire and enchant travelers from around the globe.